8th of December, 2023

LGBTQ+ people have existed throughout all of time. Some eras more heavily stigmatized them than others, but nonetheless, they have existed. Therefore, lesbian women are no strangers to having to hide their love, especially moving through the 19th and 20th centuries, as, quite honestly, being openly queer hasn’t been widely accepted until within the late 20th and 21st century. However, as such a hidden community as the queer one up until recently, it’s very difficult to find historical lesbian role models and icons, because even if their identity was apparent, it was more likely to be hidden by the individual for fear of scrutiny. However, years, decades, and centuries after their deaths, personal documents, including letters and diaries, of historical significance can reveal the identities of these figures. This leads many queer women, young and old, to find themselves within these people, making their identities feel more valid in an overwhelmingly heterosexual-dominated society. In exploring historical lesbian love letters, lesbians of all eras are able to create a connection with their once long-lost community.

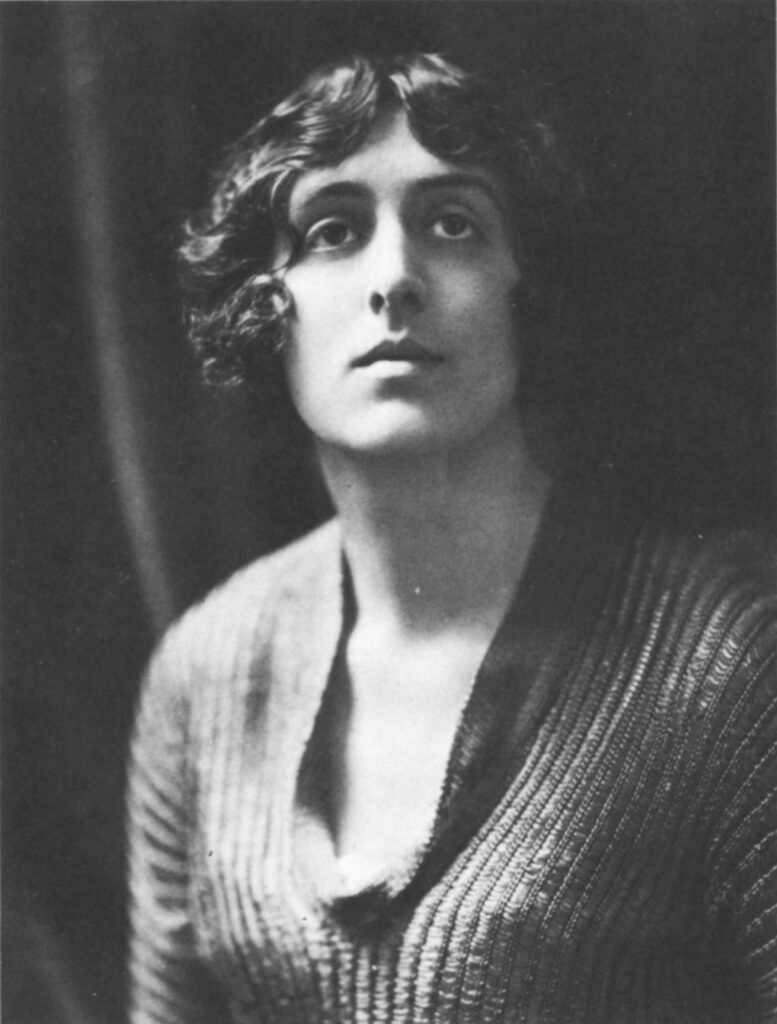

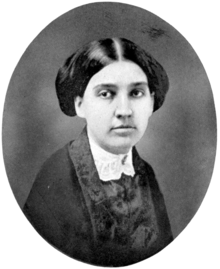

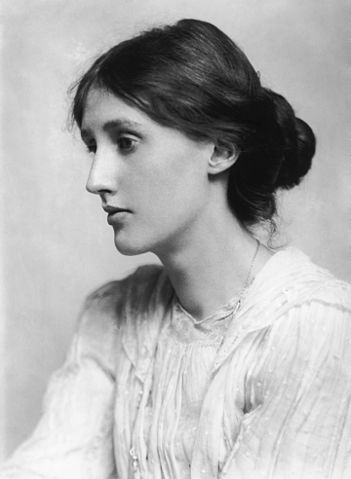

Some of these affairs through letters did not begin in person, and in fact, began via letter, some with passionate confessions, others with more hidden confessions buried in the letters’ contents. Famous historical examples would be that of Vita Sackville-West and Edna St. Vincent Millay, who both confessed to their future lovers, Virginia Woolf and Edith Wynn Matthison, respectively, via their letters after an initial fated meeting, albeit in very different ways. Sackville-West was more of the passionate type, writing to Woolf,

I shan’t make you love me any the more by giving myself away like this–But, oh my dear, I can’t be clever and stand-offish with you: I love you too much for that. Too truly

Lowenherz 60

The two women had already determined their feelings for each other, this letter being written shortly after, but the wording is undeniably confessional in nature. In essence, Sackville-West is trying to keep her love contained, as the times called for, and to not force herself upon Woolf, but she can’t. She loves Woolf too much to try to push her away with crude behavior. Similarly, though not as passionately as Sackville-West, Millay undermines her own feelings in her letter to Matthison, but it is clear she cannot contain these feelings, and she feels reciprocation on Matthison’s end. In only her first letter reply after the pair met, she quite suddenly writes:

…I know that your feelings for me, however slight it is, is a nature of love…I like to think that it is true,– and nothing that has happened to me for a long time has made me so happy…

Millay 70

Both Millay and Sackville-West express this understanding of love between them and their partner, no matter how long ago they met, and the women cannot deny: there is something between them. Something greater than close female friendship. Millay’s “I know your feelings for me, however slight it is” and Sackville-West’s “I can’t be clever and stand-offish with you” emphasize this connection. They are both willing to throw away their emotions, their lives, their dignities, to be with their clandestine lover, hiding away from cisgender-heterosexual society, creating a world solely for them.

Moreover, with this need of affection comes the case of yearning for each other through letters, dreaming of loving physical touch between the two women. No doubt, yearning appears in every love letter, a key staple of the genre, but it’s distinct in the case of queer lovers, where their love cannot be openly expressed when heterosexual love can, in both words and gestures. First lady Eleanor Roosevelt’s lover, journalist Lorena Hickok, wrote in the very first lines of one letter written after a great deal of time apart,

Most clearly, I remember your eyes, with a kind of teasing smile in them, and the feeling of that soft spot just northeast of the corner of your mouth against my lips

Streitmatter 52

Though only the faintest memory of physicality occurs in this notion, the physicality between the two is undeniable. Hickok just describing a corner of Roosevelt’s mouth brings such tender love forward, the little details making the reader understand the women’s deep affections for each other, no matter how much time they spend apart. However, even within these love letters, there is sometimes emphasis on their secretive nature in “physical” affections. Contrastingly, Emily Dickinson closes a letter to her lover, Susan Gilbert, writing:

…I add a kiss, shyly, lest there is somebody there! Dont let them see, will you Susie?

Usher 183

expressing directly the need for no one else to see their love, for it to be shared, albeit in a tonally teasing fashion. Dickinson also expresses her affections in a more subtle way, describing what their love would be once they were together again:

If you were here—and Oh that you were, my Susie, we need not talk at all, our eyes would whisper for us, and your hand fast in mine, we would not ask for language

Usher 183

Her lines, unbelievably poetic, are out of nearly every lesbian’s dream. No words. Just hands touching, eyes met. In the smallest physicalities, these women want each other, in every way love can be wanted.

Even in sentiments where physicalities are not directly expressed, only desire, the desire can be felt deep, almost carnally. Sackville-West writes,

…I am reduced to a thing that wants Virginia. I composed a beautiful letter to you in the sleepless nightmare hours of the night, and it has all gone: I just miss you, in a quite simple desperate human way

Lowenherz 60

once again passionately describing her love for Woolf. Woolf occupies her every moment, “reducing” Sackville-West to animalistic-adjacent behavior, a shark that has smelt blood, only thinking of blood, desperate for the taste. Similarly, Millay also writes of this deep desperation for the affections of Matthison, writing,

Love me, please; I love you; I can bear to be your friend. So ask of me anything, and hurt me whenever you must…

Millay 71

In spite of the punctuation, one cannot help but read these words quickly, hunger and desire leaping from them. Millay and Sackville-West seem to derive their writings from the same deep place: bleeding, hungry hearts for their loves. Dickinson also expresses carnal love to Gilbert, however, more subtly, the imagery of a heart arising from her words:

I miss my biggest heart; my own goes wandering round, calling for Susie

Usher 183

Interestingly, the nature-centric poet grabs for an organ, feeling almost gothic, bringing to the forefront deep desire and passion, but less animalistic than Sackville-West and Millay. The secretive nature of these relationships does not quell the deep, loving desires shared by heterosexual counterparts; instead, the passion seems to arise just as much, if not more so. It’s as if the danger of their love creates a more thorough sense of danger and excitement to their love. Queer love fights through, in spite of what prying eyes may demote these women to.

Why is one supposed to even care about if these women were in queer relationships? They had husbands, lives separate from their queer identity, if that’s even what it was. If they’re all dead and gone, what’s the point? The point is: it’s history. Queer history is just as important as any other history of peoples and marginalized groups. Cory Collins, former senior writer for Learning for Justice, writes,

Within these histories—and within every culture’s history—queer people lived…Throughout recorded and oral histories around the world, their stories surface

Cory Collins, Learning for Justice

and within those recorded and oral histories are the very letters written between these four couples. Due to the secretive nature of the community, being suppressed for so long, anything emerging from these periods of informational blackout is incredibly important to recognize. In addition, misrepresenting these women, straight-washing them, if you will, denies their personhood and lived experience. When analyzing and looking at historical figures, it’s important to look at all aspects of their identity to understand them further. It’s not only important for the legacy of these figures, but also for queer kids to come:

For queer students who have been made to believe that queerness is an aberration or a 20th-century invention, evidence to the contrary is validating…And by including a fuller story of queer history—a story that spans place and time, that covers celebration and resilience—we offer queer students a guidepost

Cory Collins, Learning for Justice

Looking at these women’s letters, it very much gives a comforting air to any queer person reading them. It proves they existed. It proves their feelings are valid. The letters also reflect aspects of modern queer culture and media. Though times have changed, lesbians still have the teasing air of Dickinson, Millay’s expressions of love, and Hickok and Roosevelt’s domestic affections. When histories are shared, people realize how much in common they have with the past, and even historical figures who are so drastically different from them. These first-hand accounts by letter give readers a personal dive into their lives, allowing for a deeper understanding of readers’ peers and themselves. In these letters, people can see just how much of themselves are reflected in these lesbian grandmothers.

Works Cited

Collins, Cory. “Queer People Have Always Existed—Teach Like It.” Learning for Justice, 15 March 2021, https://www.learningforjustice.org/magazine/queer-people-have-always-existed-teach-like-it. Accessed 28 November 2023.

Dickinson, Emily. Letters of Note: Correspondence Deserving of a Wider Audience. Edited by Shaun Usher, Canongate, 2013. EBSCO Host, https://web.s.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=b93e8d97-1fda-44f0-ab49-517d62a470a5%40redis&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZSZzY29wZT1zaXRl#AN=2908472&db=nlebk. Accessed 28 November 2023.

Popova, Maria. “Emily Dickinson’s Electric Love Letters to Susan Gilbert.” The Marginalian, 10 December 2018, https://www.themarginalian.org/2018/12/10/emily-dickinson-love-letters-susan-gilbert/. Accessed 28 November 2023.

Popova, Maria. “The Greatest Queer Love Letters of All Time.” The Marginalian, 14 February 2014, https://www.themarginalian.org/2014/02/14/greatest-queer-love-letters/. Accessed 28 November 2023.

Roosevelt, Eleanor, and Lorena A. Hickok. Empty Without You: The Intimate Letters Of Eleanor Roosevelt And Lorena Hickok. Edited by Rodger Streitmatter, Free Press, 1998. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/emptywithoutyoui0000roos/page/54/mode/2up. Accessed 28 November 2023.

St. Vincent Millay, Edna. Letters of Edna St. Vincent Millay. Edited by Allan R. MacDougall, Down East Books, 1984. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/trent_0116301912295/page/n7/mode/2up. Accessed 28 November 2023.

Woolf, Virginia, and Vita Sackville-West. The 50 Greatest Love Letters of All Time. Edited by David H. Lowenherz, Crown, 2002. Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/50greatestlovele00lowe/. Accessed 28 November 2023.

ZORAIDA. “NOT A PASSING PHASE: Reclaiming Lesbians in History 1840–1985 (Lesbian History Group).” Medium, 15 August 2019, https://medium.com/@sarayluna24601/not-a-passing-phase-reclaiming-lesbians-in-history-1840-1985-lesbian-history-group-4b93c6b18f56. Accessed 28 November 2023.